Like most fruits, oranges and lemons are not indigenous to North America. Originally from what is today central-China, citrus is challenged by most climates but has done well domestically in the sun-filled regions of California, Arizona and Florida. As the industry grew through the twentieth century from individuals with a few backyard trees to factory farming on an industrial scale, so did the use of insecticides, herbicides and fungicides on a similarly massive scale. Some are used as a precaution, and some are used only when groves show signs of struggle. Currently in the U.S., citrus greening, spread by infected Asian citrus psyllid insects, is the biggest threat. Since the disease was first discovered in Florida in 2005, millions of acres of trees have died because there is no known cure– once a tree is infected it dies within years. Despite pesticides having no effect, in 2021, then-President Trump's EPA approved the pesticide aldicarb for use on citrus. Aldicarb is banned in many world nations because it is known to cause cancer in humans.

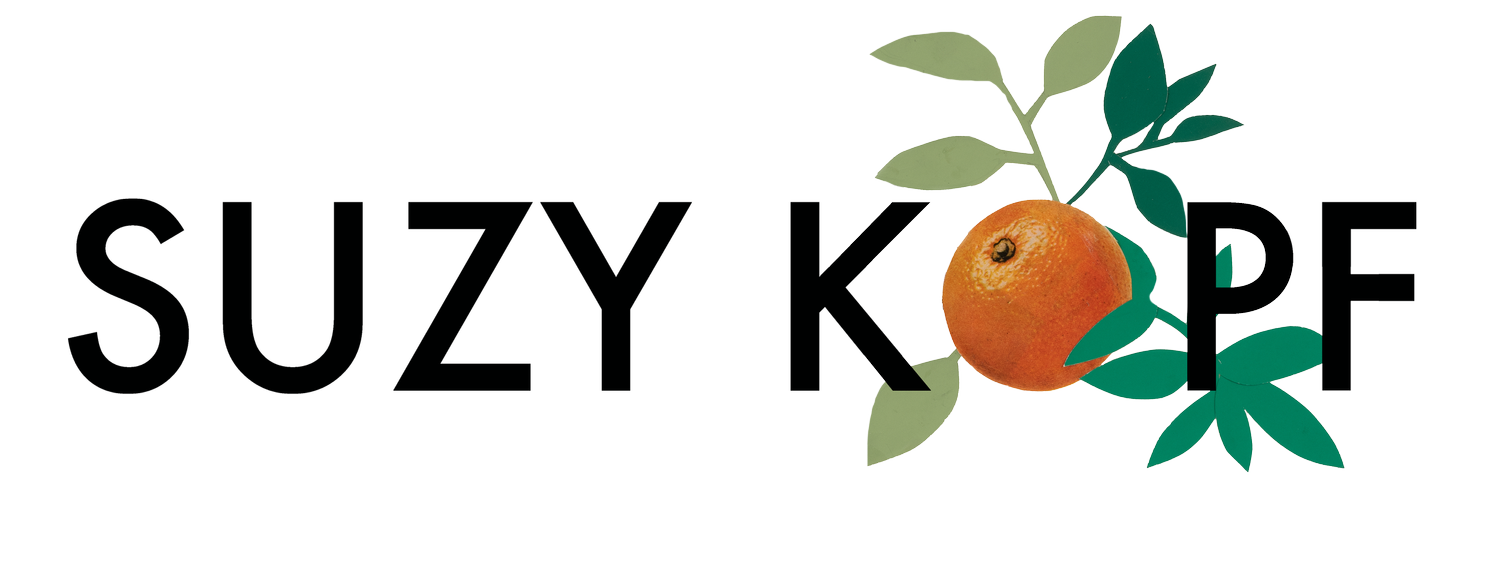

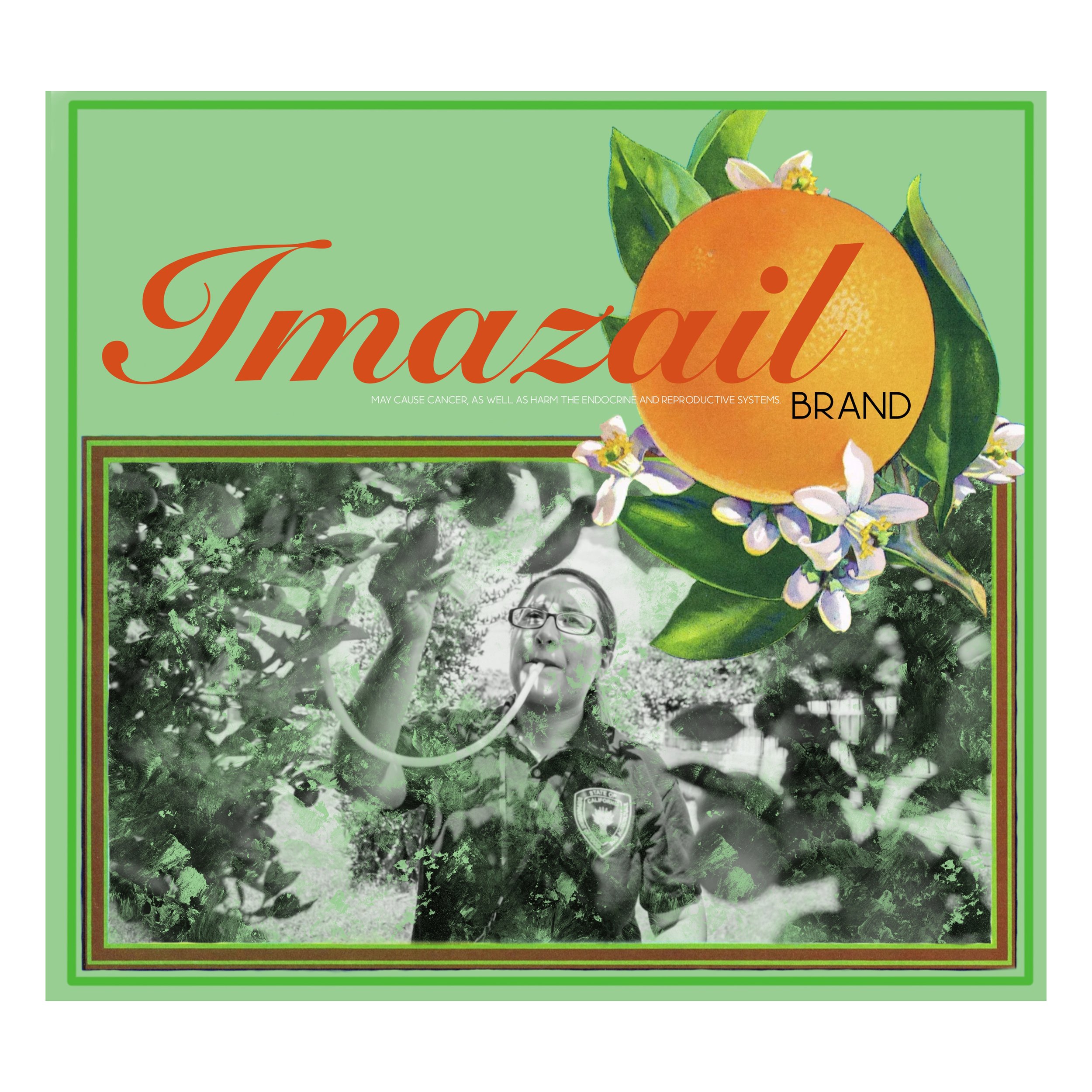

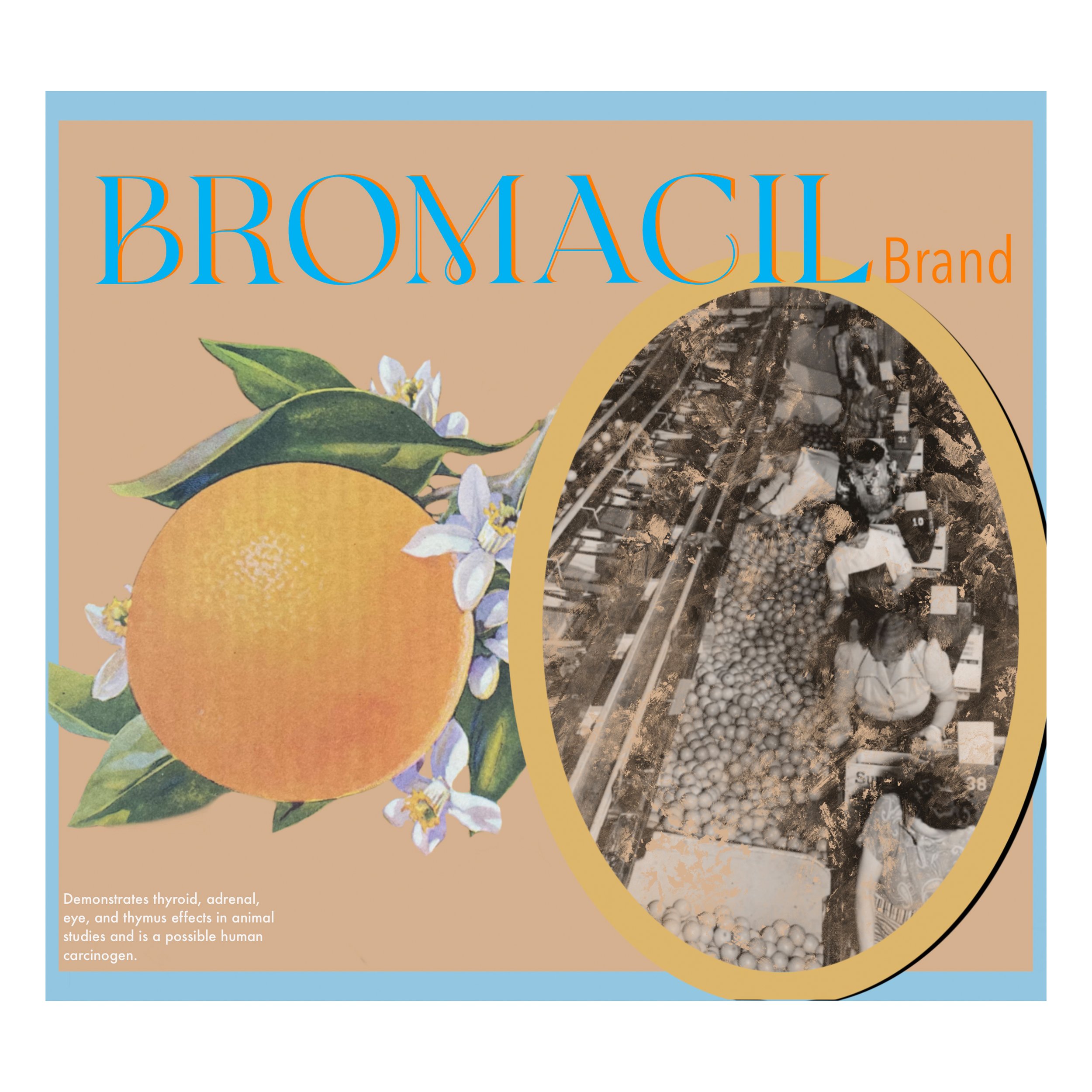

This series contrasts citrus crate labels from the 1930s and 40s with the artists’ imagining of new labels for the ten most prominent pesticides used in citriculture. The new labels play with the layouts and fonts of the old and are meant to hide in plain sight, much as the poison we ingest as a byproduct of factory farming does. The photographic imagery in the new labels depicts citrus workers, in both historical and contemporary contexts who are exposed the most to these pesticides.

10% of sales from this series is donated to The Farmworker Association of Florida and Farmworker Justice (based in California), two nonprofits working to secure labor rights and health protections for citrus workers.

Aldicarb, 2022 Digital Print, 11”x10”, Edition of 5

Arsenic, 2022 Digital Print, 11”x10”, Edition of 5

Imazail, 2022 Digital Print, 11”x10”, Edition of 5

Methomyl, 2022, Digital Print, 11”x10”, Edition of 5

Thiabendazole, 2022, Digital Print, 11”x10”, Edition of 5

Bromacil, 2022 Digital Print, 11”x10”, Edition of 5

Oxamyl, 2022 Digital Print, 12.5”x9”, Edition of 5

Benomyl, 2022 Digital Print, 12.5”x9”, Edition of 5

Streptomycin, 2022 Digital Print, 12.5”x9”, Edition of 5

Fenbutatin, 2022 Digital Print, 12.5”x9”, Edition of 5